October 13, 2011, 5.30 pm, New Delhi:

Night comes in like a disease in New Delhi, mosquitoes bring it in on their backs. As darkness falls stray dogs dodge blaring traffic and beggars melt into the roads. A bear dances for its supper in a stinking alleyway.

Then the lights go out.

Yes, the ninth biggest city in the world has just had its tenth power cut of the day. They say its because the golden office block in Guargon is draining all the electricity, it is festooned with millions of bulbs for the Festival of Light after all. Only it and the Mercedes Benz decal suspended high above the city still fizz against air so polluted it chokes out the moon and the stars. Twenty million of us, beggars and businessmen, travellers and tramps, the gullible and the gurus, scurry like cockroaches in the dark.

This city will make you ill, there’s no doubt; if the mosquitoes or bats, gone insane because of rabies, don’t get you then the money will. People talk about filthy lucre but their ain’t no money as dirty as a 10 rupee note.

The problem is the lack of sanitation. People go behind market stalls or in the gutters outside the run-down old colonial stores with names like Ye Olde Shoppe, and bring a whole new meaning to hand wipes. The detritus of life is transferred to the cash in their pockets. Ten rupees is worth pennies but in a desperate city like this it buys polluted water and rotten veg.

Ten rupees is the true price of Delhi Belly.

A tuk-tuk keeps a constant bleat on its horn as it weaves its way through families, tramps and gurus, sacred cows, pigs and snuffling canines, cars, bikes, multi-coloured juggernauts and sweating rickshaws.

I’m standing on the baking pavement outside New Delhi rail station. I’ve just disembarked from the overnight train from Nepal, I can still see it steaming like an old snake by the platform, brittle paint like dry scales.

The skin-and-bone one eyed tuk-tuk driver stops less than a hand’s length away from me and croaks through the dust in suprisingly cultured English: “You would like a lift Sir? I’ll take you where you wish to go.”

It makes sense to escape this cacophony, so I jump on board. In a way it was bound to be a mistake – the bench seat is ripped and smells of damp, ideal for cockroaches. And immediately one scurries across my lap. It’s as big as a thumb. The driver reaches over and squashes it between his fingers, a white liquid spurts as he pelicans it away.

“Sorry sir,” he smiles and turns his head to face me, once again he surprises me; he must be a hundred years old!

“I try to keep them at bay, I’m a clean driver.” I have to turn away, I feel sick to my stomach as he licks the remnants of the cockroach from his fingers.

Then I see that the bicycle tyres taking me to my destination are bald and some of the wheel’s spokes are missing. Tuk-tuks are three-wheeler bikes with a canopy and motorboat engine and they may be just about the cheapest and most dangerous form of transport known to man.

The driver’s horn bleats like an angry sheep as he begins to weave his way back into the madding crowd. I keep one eye on the road and the other looking out for cockroaches …

Driving in Delhi is like the rest of the city, on the face of it it makes no sense at all but underlying it there’s a reason and the reason is symbiosis; everything, from sacred cows to corrupt coppers, fakirs and gods and ghosts rub along. Driving is no different, it is a mercurial waltz, a liquid dance of metal and man, tuk-tuk, car and lorry, bicycle and beast sliding round each other with a syncopated rhythm – and the constant blasting of horns isn’t aggression, its a beat, a marking of time, it quickens or slows the dance.

We are weaving our way through Karol Bargh on a multi-lane highway parallel with the ancient railway sidings filled with rusting carriages, gantries and rotten derrick cars, craning like the skeletons of giant birds. It’s a sorry sight.

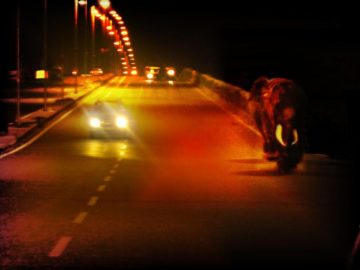

Then I witness the oddest thing; an ancient elephant lumbering slowly through the traffic. Stranger than it being there though is its appearance; it seems diffused, somehow insubstantial, shimmering darkly as if not quite formed. It strikes me instantly that it’s like watching it on the dirty grey screen of the backyard cinema I visited in Jaipur …

But it is more inexplicable than an old cinematic trick, all at once this creature is there and yet it isn’t.

I look at the driver, he seems deliberately oblivious, yet nervous about this mammoth apparition.

My attention is drawn away from it for a second as Delhi lights up again – the city always comes back to life after a power cut like this, it returns like fire, tiny incendiary moments inside the myriad windows of thousands of towering monuments to high-rise living, the high and the mighty above the despair and dirt on the streets. Phut! they come back on, Phut! Phut! Phut! – one after the other families see the light of the 21st century again … phut! Banks of street lights, the dark ages are banished for another couple of hours Phut! greasy cafes, Phut! Phut! Phut! commerce comes back on line. The golden office block might glow dimmer but once again Delhi is a real festival of light.

And the elephant is gone.

I turn to the driver: “Did you see the elephant? Where did it go?”

This time he doesn’t look back at me, just says quietly: “I have one eye sir, I see only what I see.”

He sounds as ancient as the hills.

August 1947, Delhi

The partition of India and Pakistan is rushed through. The malaria sky is filled with booms, then bangs and flashes, silvers from the barrel of a gun, violent ends to lives that nobody cares about anyway. This is murder and horror. Connaught Place disappears under riots and refugees.

Delhi has the biggest refugee camps the world’s ever seen, conservative estimates say that at least 12 million people have been made homeless almost overnight, thousands crowd the Delhi Rail station trying to catch a ride to the South.

More than a million Indians are dead in the streets.

British interference in the world is at its worst. Viceroy Lord Mountbatten of Burma has reduced the partition process to a shambles and, while he’s doing it his wife, Edwina, is having a ‘holiday’ romance with India’s new prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru.

Everything is chaos and new frontiers like these always attract Men like John Mackenzie Cameron. John Mackenzie Cameron a dealer of indeterminate age with a frankly-I-don’t-give-a-damn moustache and a diamond as big as a shoe. He was a mad dog in any midday sun.

John Mackenzie Cameron dealt opium and cheap Stag whiskey to the new colonials and they loved him for it. And his devil-may-care black patch he wore to hide his empty eye socket. He lived in the dusty decaying suburb of Karol Bargh with a young prostitute of questionable gender. All night long mad dogs and rabid bats battered against his windows and gates, But he didn’t care, he revelled in the mud and the dust and the blood and the beer.

His dented old Buick 6, flying skull and crossbones on its wings, was driven by Usef, a diminutive Bengali whom, it is said, he beat with a silver topped cane. However, Usef took Cameron to the places he needed to go, places few white men would ever visit. In Delhi, way back then, that was where the deals were made, in the shadow of a dancing bear or under the wings of a flying god.

John Mackenzie Cameron was a thoroughly bad lot much needed by his ex-patriot peers. Oh, and how they must have laughed and raised a glass to his last known act on this earth. And that was to hang an Indian elephant by the neck until it died.

This is how it happened.

In 1947 the road along side Karol Bargh was only slightly worse than it is today. Of course there was no pock-marked multi-lane highway, back then it was a dirt road as bad as the face of the moon. The dust at night was thicker than London smog.

The lights on the old battered Buick 6 had failed long ago but Usef drove at break-neck speed through the gloom with his master bouncing and raging in the back seat waving his silver topped cane around and making incoherent threats against the night. In this land of fatalism Usef and his master were an accident waiting to happen. And it did.

Something shimmered ahead, as if not quite formed…

… the Buick 6 smashed into the elephant’s legs like a giant axe smashing into the trunk of an old oak tree. The elephant bellowed in pain.

Then in a split second of self-preservation and rage the creature reached down with its trunk into the car and hauled the driver twenty feet into the air before dashing him down into the dust. Usef’s head burst like a blood-red water melon across the road.

But because its legs were shattered this beautiful, massive sensiant creature crumpled – its great gnarled knees crashed down onto the bonnet of the Buick, its grand and powerful head smashed the windscreen to smithereens and its massive trunk lashed the interior.

John Macenzie Cameron launched himself out of the vehicle into the dirt where he lay as the creature let out a breath as hot as steam. Its eyes locked on the terrified man’s one bloodshot orb. He knew at that moment that he had to remove his car from the scene. And he also knew this elephant would never forget him.

When the sun began to rise behind the dust the very next morning there wasn’t a telltale sign of John McEnzie Cameron or his wrecked Buick 6, it was gone. And Usef’s life-blood had all but blown away in the warm winds of the night.

***

As the day became alive the tortured, the dispossessed, the refugees and even the colonialists stood together in silent awe. People traipsed from the centre of Delhi to stand before this horror.

The injured elephant had been hanged by the kneck from a rusting old derrick car which had been driven from the railway sidings across the road. It’s neck was stretched like leather and its trunk hung impotently. The animal looked for all the world like a child’s knitted toy hanging from the hook on a door. But its eyes were still open …

***

After this story had been related to me by an old chap in a former gentleman’s club, now a cheap strip joint down an alley off Connaught Place, I went back to New Delhi rail station to see if I could find that ancient tuk-tuk driver with the perfect English accent.

But it was bound to be an impossible task … hundreds, maybe thousands of tuk-tuks were scurrying around like busy green ants. The mysterious driver with one eye might as well have never existed.