Tough guys don’t dance when PA punches their lights out

I am a Manc, a back street boy born to be tough. Moston was my teenage hunting ground.

That’s North Manchester where footpaths were either made out of cobbles or broken bricks and windows. Suburbs of terraced houses, urban regeneration, mud holes and smoking guns. Toothless wives in elastic stockings, smoking Park Drive dimps, dads with death-rattles in their chests stumbling drunk out of The Thatched, The Museum, The Ben and The Bricklayers Arms… t

These were all my roll models.

Yep, this was our King Cotton town in the Sixties and the 70s.

There was One-Eye Jack who’d had his right eye sewn together for more than a decade. It gave him a wicked wink. Jack walked three miles from Newton Heath every day to drink gallons of John Willie Lees at the Blue Bell.

Brian ‘The Bear’ Dunn liked to throw fellow drinkers through pub windows, Brian Poole – who looked like Frankie Vaughan – would grin himself into a coma at the bar, Johnny White Boots liked to pour beer pover people’s heads to start a fight, Dougie Flood and his Quality Street Gang, Jimmy Swords and his cohorts holding war talks in the back room at the Galleon Restaurant on Kenyon Lane.

Peter Tut Tut, Savage Brian and Savatsi might not be street fighters but, like all Mancs, they knew how to look the part. Viagra for the eyes, it makes you look hard.

Yep, rainy North Manchester. At least brought you up tough and rough and ready for anything.

Except being kept from seeing your children by a cuckolded angry ex.

Nothing prepared me for that.

And nothing prepared me for it happening again thirty years later, this time in a pretty little cottage down a lane in the backwaters of Shropshire.

Three children used like an arsenal of emotional bombs by two mothers who just wanted to sit there nibbling Jammy Dodgers and watching Emmerdale while they ladled revenge like cold curdled soup.

I eventually got my children back after many years. But for so long afterwards there was a barbed wire fence between us. It was festooned with lies and fabrications, vitriol and bitterness. Like a bridge of broken locks.

To this day I believe that the scars of the lies their mothers and their families told, still sometimes turn the light black inside my children when we meet.

But despite the drink, the drugs, the insecurity, the worry, the lack of income after paying maintenance, the ‘gifting’ of houses to women who no longer wanted to share my life, I survived.

Some of us don’t.

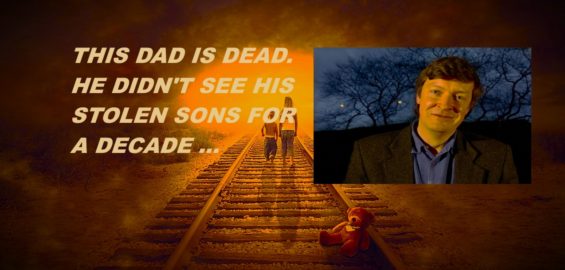

Douglas Galbraith, a fellow writer, didn’t.

Douglas Galbraith is now dead and not even a stain in the universe.

In 2003 he arrived home from a work trip and was expecting to be greeted by Japanese wife Tomoko and his two sons, Satomi, aged six, and Makoto, aged four.

The doors were locked and Douglas had to break in.

But the house was stone cold and empty. The only clue to what had happened was a Royal Mail letter on the doormat confirming instructions for forwarding post to Tomoko’s new address in Japan.

Douglas had lost his children and he would never find them again.

For years he hammered away at the Japanese courts, the British government and lawyers. He wrote a book about the loss in the hope that they might one day see it, and contact him.

It never happened.

In 2018, Douglas killed himself. He was 52 and hadn’t seen his children for 15 years.

But the battle over them still goes on. On behalf of their grandmother and family, his sister Karen Macgregor, from in Glenborrodale in the western Highlands, is continuing the search.

She has hired a private investigator in Japan,

Karen says. ‘I remember visiting his home and realising it had become nothing more than a shelter. It was devoid of life and love. We could not believe that anyone could be so cruel.

‘He was a loving father and family. She was denying a father the right to love and support his children and she was leaving a family broken and in limbo.. At first, we did not know how to console and support him.’

Douglas had met his wife, Tomoko Hanazaki, at Cambridge.

In his memoir, My Son, My Son, Galbraith he describes their marriage as having descended into ‘an openly declared and exhausting war for the past five years’.

Douglas thought he had a major breakthrough when Interpol tracked Tomoko and the children down to a temporary address in Osaka. Then they moved police refused to give him their new address.

One of the problems was that in Scotland – unlike in England and Wales – child abduction is not an offence unless a residency order is in place.

And Japan is not a signatory to the Hague Convention on Child Abduction.

In 2013 all contact was lost.

Later Douglas was forced to sell his house to to send money to Tomoko to support the children.

‘Tomoko now has the children and the money and before long the telephone, predictably, goes dead,’ he wrote in his memoir. ‘It has been an expensive exercise. They were worth it.’

Douglas died in 2018. He hadn’t spoken to his sons for nine years.

My name is Finlay Satomi Galbraith Hanazaki.

Douglas Galbraith is my dad… (temporarily held back for verification)

Will get back to you Findlay … thank you

Appreciated, i’ll be on linkedin + twitter, 247